For more than 30 years, a small parcel of land covering about 45 square miles (116sqkm) has had an outsized impact on the way we work, live and play.

California’s Silicon Valley shapes our lives. From the websites where we do our household shopping to the video-streaming services we watch to the companies which provide our email, almost all are based in this corner of the United States.

Until recently, that is. The rise of TikTok, an app whose parent company is the Chinese firm ByteDance, has struck at the heart of Silicon Valley’s supremacy. Along with other digital products coming out of China, TikTok has the potential to reshape the future of technology – a future in which the culture, and the interests, of Shanghai or Beijing could mould the industry more than that of San Francisco Bay.

It’s hard to overstate just how much of a switch this is.

You might also like:

- How East and West think in profoundly different ways

- Is social media bad for you?

- The hidden things your apps know

“The narrative previously was about China coming up with its own versions of [Western] digital products,” says Elaine Jing Zhao, senior lecturer in the school of the arts and media at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

“Nowadays, you see the narrative shift towards how Western social media platforms are learning from Chinese social media platforms.”

And Chinese apps, platforms and services currently look quite different from those in the West.

The rise of Chinese tech

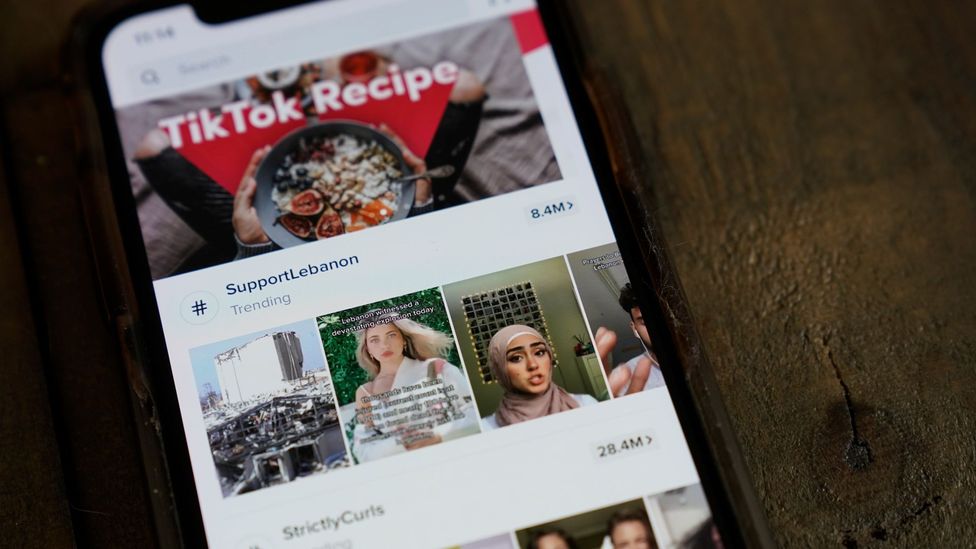

The most famous, of course, is TikTok – which has 690 million monthly active users worldwide, 100 million of whom are in the United States and a further 100 million in Europe.

TikTok has 690 million monthly active users around the world, including 100 million in the US and another 100 million in Europe (Credit: Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Like other apps of Chinese origin, TikTok’s owners have tried to downplay the app’s background. “They want to give international users the impression they are not Chinese platforms, but global platforms,” says Jian Lin, assistant professor at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, an author of multiple books on the Chinese influencer industry and technology platforms. “They really want to transmit this impression to the public that they’re not necessarily Chinese. They’re just like others, a global platform.”

Their fear of backlash has been borne out by the hard stance US President Donald Trump has taken against the app, who claimed without significant evidence it’s a national security risk. Other countries to oppose TikTok include India, where the app was banned in June 2020, and Pakistan, which banned it for 10 days in October.

Demonstrators urge citizens to remove Chinese apps from their phone in New Delhi in June 2020 (Credit: Prakash Singh/Getty Images)

But these challenges seem unlikely to dissuade other Chinese tech companies from following TikTok’s lead, says Lin. “I do believe Chinese companies will become even more ambitious and stronger in the coming years,” he says.

He also expects these companies to increase their global ambitions: since the Chinese domestic tech market is highly saturated, with strong levels of competition, they may see more opportunities coming from the overseas market.

Changing Western tech

Already, the way Chinese-launched apps interact with users, and the services they offer within the apps, are influencing Western platforms. One example: the “superapp”.

“In China it’s very common to become a superapp, where you do a lot of different things within the same app,” says Fabian Ouwehand, founder of Many, a Dutch social marketing agency that advises companies and influencers on how to use TikTok and its Chinese version, Douyin.

Perhaps the most popular combination? Social media and commerce. “In China people are used to the commercialised version of social media entertainment, and do a lot of ecommerce and business through their apps,” says Lin.

On Douyin, for example, users can buy products directly from the app as they watch the shortform videos that creators post onto the platform – something TikTok in the West is mimicking through the introduction of integration with online shopping platform Shopify, launched in October 2020. WeChat, which is often described solely as a chat app, is far more: it’s also a payment platform and a way to keep up to date with friends.

The reason superapps have become so popular in China is simple, says Zhao. “People feel it’s really convenient to have every part of their life organised by social media platforms and superapps,” she says. “From shopping online to hailing taxis, socialising with friends and meeting up with strangers, everything you can do within one app.”

People walk past the Beijing headquarters of ByteDance, which owns TikTok, in September 2020 (Credit: Greg Baker/Getty Images)

This kind of approach requires handing over more data to link up disparate systems into a single, convenient place for users – something that not everyone might be comfortable with. But experts believe that the demographics are on the side of app developers. “Younger users will accept it quicker than the older generations, who are a little bit wary,” says Ouwehand. “They value convenience over privacy.”

Western companies are taking note. Platforms like Facebook have begun to bring various features and services under a single umbrella: in recent years, Facebook has integrated online video (Facebook Watch) and shopping (Facebook Marketplace) into its core social network. Instagram, owned by Facebook, has added TikTok-like shortform repeating videos, called Instagram Reels, in recent months, and also has a connection with Shopify so fans of influencers can buy products their favourites wear directly in the app..

“I’m seeing more and more companies trying to add more features into their apps,” agrees Rui Ma, a Chinese tech expert based in Silicon Valley. “That’s probably the biggest overt move that looks a little bit more like Chinese tech.”

Enhanced moderation

But, behind the scenes, there are other differences that could also make meaningful change.

TikTok has been criticised for its approaches to disabled and overweight creators, whose videos it has been alleged to de-prioritise – a legacy of moderation policies drawn up by staff in China. The app says it has since redrawn its policies on moderation to accommodate a more open, less censorious Western taste and culture. (Read about how social media affects body image).

“What we know based on media reports indicates TikTok has very clear guidelines within their own company of what kind of content to promote, and what kind of content should be deleted or hidden from other users,” says Lin.

TikTok user ‘Ghoulbabyghoul’ records herself in Madrid in 2020 (Credit: Eduardo Parra/Getty Images)

Yet despite localising its content moderation policies, TikTok remains much more proactive than Western social platforms in intervening where it sees potentially troubling content. The company’s September 2020 transparency report shows that, of the 104 million videos removed from TikTok in the first half of 2020, 90.3% were removed before they received any views – and 96.4% were taken down by the app itself, before being alerted to infringing content by another user.

Compare that to the content moderation policies of, say, YouTube. Until the coronavirus crisis compelled YouTube to rely far more on automated moderation rather than human intervention, the app lagged a little behind TikTok on its proactive takedowns of videos. In the three months between April and June 2020, the most recent data available, 95% of videos were taken down by “automated flagging”, though only 42% had no views before they were removed.

Algorithmic recommendations

Another way in which Chinese social media platforms are influencing Western ones is in how they present and filter information.

While Facebook and Twitter recommend posts based on what your friends are posting and sharing on your news feed, TikTok and other Chinese apps like it try to learn as much as it can about you, and then direct content to you they think you’ll like. “In China you see a lot of different platforms coming up that are way more focused on exploration, and here it’s a lot on your social circle,” says Ouwehand.

A man walks past a Beijing restaurant which offers a discount to anyone who posts videos on TikTok (Credit: Greg Baker/Getty Images)

This model understands our preferences based on prior behaviour with videos we’ve already seen, rather than assuming our interests based on those we interact with or via our past search terms. It’s a meaningful difference that is shaping the way we consume information, and changes the economics of those creating the content.

Under the Chinese model of algorithmic exploration and recommendation, users are less beholden to the individual content creators they follow. On YouTube, for examples, big personalities have become celebrities because of their ability to build a loyal fanbase. But on TikTok, anyone can become a star overnight because of a single video that proves popular with the app’s algorithm – and that fame can disappear almost as quickly when the next big video is surfaced through the app’s code.

Given how popular that strategy has been, it could signal a broader change among other social media platforms, as well.

The future of tech

If Chinese companies continue to play an increasingly influential role in tech, our online world could look very different by, say, 2030.

For one, it could be much more diversified than the Silicon Valley standard we still, largely, see now. And while Chinese apps are best-known right now, that could change. “It’s not just Chinese companies, but other companies in Asia,” says Zhao. “These regional giants might want to have a slice of the global market pie as well. We’re seeing Facebook and Google competing for a slice of the Asian market, but at the same time local giants are entering the US market as well.”

A man cycles past Tencent, the parent company of Chinese social media giant WeChat (Credit: Greg Baker/Getty Images)

We might also see apps having an increased emphasis on localisation, something we already see with TikTok. “If you want to be a global company, you’re serving different consumers with different cultural tastes,” Zhao says.

And we may see Western products taking more of a lead from successful strategies or services out of China, and the rest of Asia. “That’s where the West is going to copy a lot,” says Ouwehand. “In terms of functionalities and the expansion of their own apps to do more.”

The future of technology in the next decade will certainly look a lot less like the Silicon Valley-designed ideal we’ve been used to in the last 20 years. But it seems likely it will evolve through small steps and minor influences – as evidenced through the way TikTok differs from Douyin, and the lag in changes in the Chinese version of the app making their way to the Western one.

This is, after all, how a globalised world works, Zhao says. “It’s an example of cross pollination. Doing business is always about drawing inspiration from each other,” she says.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"Media" - Google News

November 17, 2020 at 03:00PM

https://ift.tt/2IHVjvk

How China could shape the future of technology - BBC News

"Media" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2ybSA8a

https://ift.tt/2WhuDnP

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How China could shape the future of technology - BBC News"

Post a Comment