Lagos. 14 October 2020. The atmosphere is electrifying. On a regular day, Lekki toll gate in Lagos wears a different cloak; vehicles line up along interminable queues. There are no queues today. No one is hooting their horn to urge the toll workers to do sharp sharp make pesin commot here abeg (“Hasten up so we can all leave here”). The toll gate is blocked from both ends for the #EndSARS protests against the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (Sars), a Nigerian police unit, due to claims of police brutality. Demonstrators are singing along to the chorus of African China’s 2006 hit Mr President. One man is twirling his white T-shirt, now browned with sweat around the armpit region, in the air. Another holds a banner that reads “Stop killing our dreamers. #EndSARS now.” The DJ switches to Timaya’s Dem Mama, released in 2007, and, while conscious of the risks of the Covid-19 virus, young people sing along to songs that are more than a decade old without skipping a verse or mixing up the lyrics.

More like this:

- The instrument that ‘aided espionage’

- The album that defined an era

- Pop’s most underestimated icon

It is intriguing that songs critiquing Nigeria’s first eight years of a return to democracy under Chief Olusegun Obasanjo (from 1999 to 2007), after 16 years of military rule, still ring true to the present realities of the country and its citizens: widespread corruption, a high poverty rate and widening inequality gap, a skyrocketing unemployment rate, authorities clashing with protesters and detaining journalists, electoral violence, and, of course, accusations of police brutality. Barely a week after the protest I joined, on 20 October 2020, demonstrators at Lekki toll gate would be singing the Nigerian national anthem and waving the country’s green-white-green flags as officers of the Nigerian army opened fire. While Amnesty International says 12 people were killed, and multiple eyewitnesses have told the BBC they saw soldiers shoot people, the army has claimed its soldiers were firing blank bullets.

The Lekki shooting: In footage shared on social media, shots could be heard as protesters sat down, locked arms and sang the national anthem together (Credit: Getty Images)

Music and protests are inseparable in Nigeria. The history of this intersection is evident in our folklores and moonlight stories. For instance, Ojadili, a popular Igbo myth, tells the story of a warrior whose strength is drawn from the music of his personal flautist who accompanies him to the numerous wars he fights to defend his village from invasion. During the Biafran war (a civil war in Nigeria from 1967 to 1970), music was an important tool to serve as a cohesive force on the Biafran side even as they continued to incur more casualties, death, and hunger.

Cultural and political commentator Nduka Dike offered beautiful reflections on this era in his podcast about Igbo culture. He tells BBC Culture that songs were key during the Biafran war in boosting morale and translating complicated messages and manifestos for the general population. Not everyone can understand the Aburi Accord (agreed between opposing sides in 1967, its breakdown led to the outbreak of the war), and songs like Mu Na Nwannem Gara Aha (“Me and my sibling went to war”) – which was popular in the training grounds of Biafran soldiers – helped create a wider understanding.

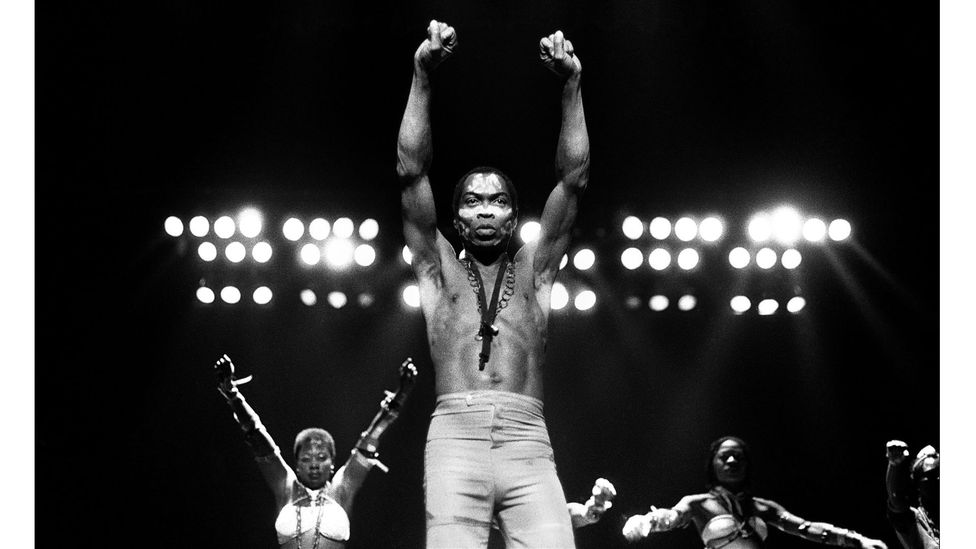

After the war, as Nigeria regenerated into a series of oppressive and corrupt military and civilian adminstrations, musicians like Fela Kuti, Peterside Ottong, and Ras Kimono gained popularity with Afrobeat and Nigerian reggae, musical styles and expressions that resonated with the plight of Nigerians. Their songs formed the soundtrack to a series of anti-government protests organised during that era. Growing up during Chief Olusegun Obasanjo’s administration, and having civil servants and union members as parents, I memorised popular chants like “Solidarity forever we shall always fight for our rights” and “We no go gree o!” used by working-class Nigerians to demand better pay and working conditions.

Why is music so much a part of protests in Nigeria? For Ikenna Emmanuel Onwuegbuna, a musicologist and senior lecturer at the University of Nigeria Nsukka’s department of music, the relationship between music and protests is easy to understand. “The African child is conceived, nurtured and raised in rhythm,” he told BBC Culture. “Pestles pounding, dance, and singing [conveys] rhythm to [the] foetus. The first communication between a mother and child is music. Music follows us from the womb to the tomb. Since music is an integral part of life, it is not atypical for it to be present in something that is equally important to our lives; protests.”

During the #EndSARS protests, there was a resurgence of interest in Fela Kuti’s songs, such as Zombie, Beast of No Nation, and Coffin for The Head of State (Credit: Getty Images)

In a recent article reflecting on the music of the George Floyd protests in the US, Mariusz Kozak, Assistant Professor of Music at Columbia University, explained how “music functions as a social glue that binds the minds and bodies of those who create it”, thereby creating a unification of purpose which is key for the sustenance and success of social justice protests. During the #EndSARS protests, there was a rediscovery of music both on and off the protest grounds, with a resurgence of interest in socially conscious songs like Zombie, Sorrow Tears and Blood, Beast of No Nation, and Coffin for The Head of State by Fela Kuti, Jailer by Asa, Mr President by African China, Dem Mama by Timaya, and Nigeria Jaga Jaga by Eedris Abdulkareem.

Songs like these are an important driving force for the movement because of clear, powerful messages that criticised an oppressive government at the time of their release. Kuti’s Beast of No Nation was released during President Muhammadu Buhari’s regime as Nigeria’s military head of state (1983 to 1985), and serves as a commentary on what was perceived to be the autocracy of the then military government, a forerunner of Buhari’s current administration.

In a country where history was removed from basic school curriculums between 2007 and 2019, Nigerians are learning key historical events (for example, the 1999 Odi Massacre, which is the focus of Timaya’s Dem Mama) through these songs. There are also softer versions of this socially conscious music that inspire hope and pride in Nigeria and Nigerians; The Future (We’re Nigeria) and The Land Is Green by TY Bello, and Originality by Faze. But it’s not the only type of music that drove the #EndSARS protests. Nigerians love gbedu (meaning “big drum”, a word that has come to describe types of Afrobeat and hip hop), even while protesting. So dancehall songs like Davido’s Fem, Tiwa Savage’s Koroba, Ogene by Zoro featuring Phyno and Flavor, and Killing Dem by Burna Boy and Zlatan, were so prominent during the protests to keep morale high.

Artists such as Asa (pictured) have used their social media and art to amplify the reach of the #EndSARS protests within and outside Nigeria (Credit: Getty Images)

In an essay published in October on The Conversation, Florence Nweke – a researcher and music lecturer at the University of Lagos – posits that protest music and the involvement of musicians in social justice protests in Nigeria has waned. For the music scholar, “The failure of Nigeria’s current pop stars to identify with the country’s oppressed has inspired feelings of nostalgia about the late Afrobeat pioneer, Fela Kuti”. This claim does a disservice to the role of Nigerian musicians like Don Jazzy, Asa, Falz, Tiwa Savage, Tems, Burna Boy, Lady Donli, Innocent Idibia (TuFace), MI Abaga, Flavour, and Phyno, who have used their social media and art to amplify the reach of the #EndSARS protests within and outside Nigeria and were also present on protest grounds. End Sars by Fikky, which started as a sample that went viral on Twitter, was adopted as the unofficial anthem of the protests. Musician and activist Eromosele Adene (EromZ) was also arrested by the police.

The #EndSARS protests might not have adopted a musician (or celebrity) as its face because in the past, the Nigerian government has been perceived as scapegoating musicians whose songs offered social commentary by banning or censoring their music. As Nweke acknowledged, under military rule, “Most of Fela’s songs didn’t receive mass media rotation. Peter-side Ottong’s music was banned. Ras Kimono’s songs were blacklisted or ‘not to be played on air’ by state-owned radio stations.” And Falz – who is both a rapper and a lawyer, with 7.4m followers on Instagram – spoke out recently about the #EndSARS protests. He described the beginning of the protests to CNN’s Christiane Amanpour: “On 8 October, myself and another artist named Runtown, we had shared on our Twitter and Instagram pages that we were going to do a walk, just a march – a peaceful protest against all forms of police brutality… We did that with the hashtag #EndSARS. The hashtag was already in existence. This was something that was already a big thing on social media, but no one had actually gone ahead to do a physical protest, so we decided to take that extra step.” Whatever happens next, in whatever way Nigerians choose to stand up to systematic oppression and violence, there will always be music; in the words of Dolly Parton, “as long as there’s a story to be told”.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"social" - Google News

December 09, 2020 at 07:32AM

https://ift.tt/2VX6uTD

How music is intertwined with social justice in Nigeria - BBC News

"social" - Google News

https://ift.tt/38fmaXp

https://ift.tt/2WhuDnP

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How music is intertwined with social justice in Nigeria - BBC News"

Post a Comment