In middle school and high school, Nora Tan downloaded the big three of social media. It was only natural. “I grew up in the age when social media was really taking off,” says Tan, a Seattle-based product manager. “I created a Facebook account in 2009, an Instagram account in 2010, a Twitter account after that when I was in high school.”

By the time she reached college, Tan was questioning her decision. “I thought about how content should be moderated and how it was being used in political campaigns and to advance agendas,” she says. Troubled by what she learned, Tan deleted Twitter, used Instagram only to follow nature accounts and close friends, and downloaded a Chrome extension so that when she typed in Facebook on her search bar, she was only served notifications from her friends.

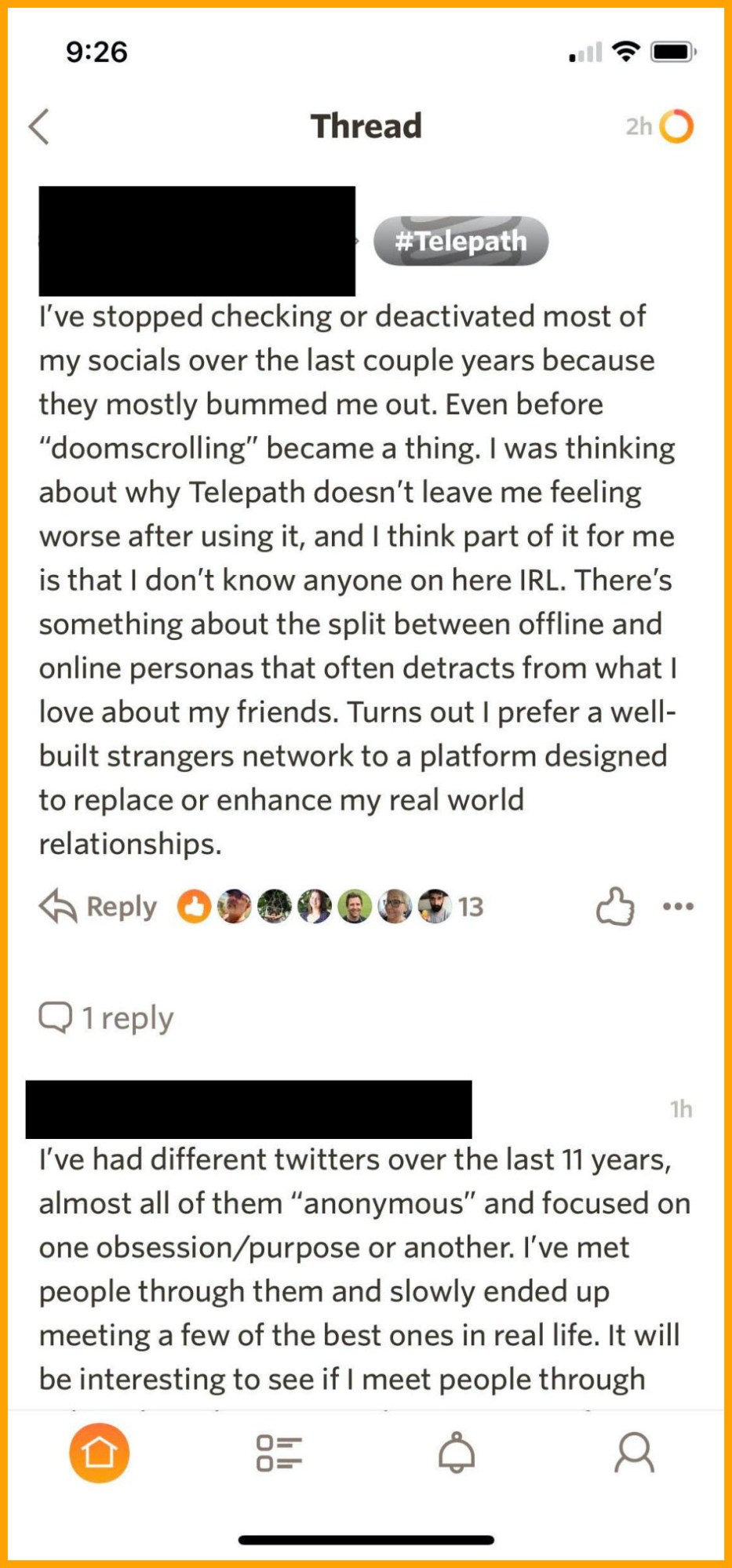

So she was “pretty cynical” when a friend invited her to be a private beta tester for a new social-media platform, Telepath, in March 2019. She was particularly skeptical as a woman of color in tech. Eighteen months on, it is now Tan’s only form of social media.

Telepath was cofounded by former Quora head Marc Bodnick, and it shows—its format feels similar to Quora’s in some ways. The invite-only app allows users to follow people or topics. Threads combine the urgency of Twitter with the ephemerality of Snapchat (posts disappear after 30 days).

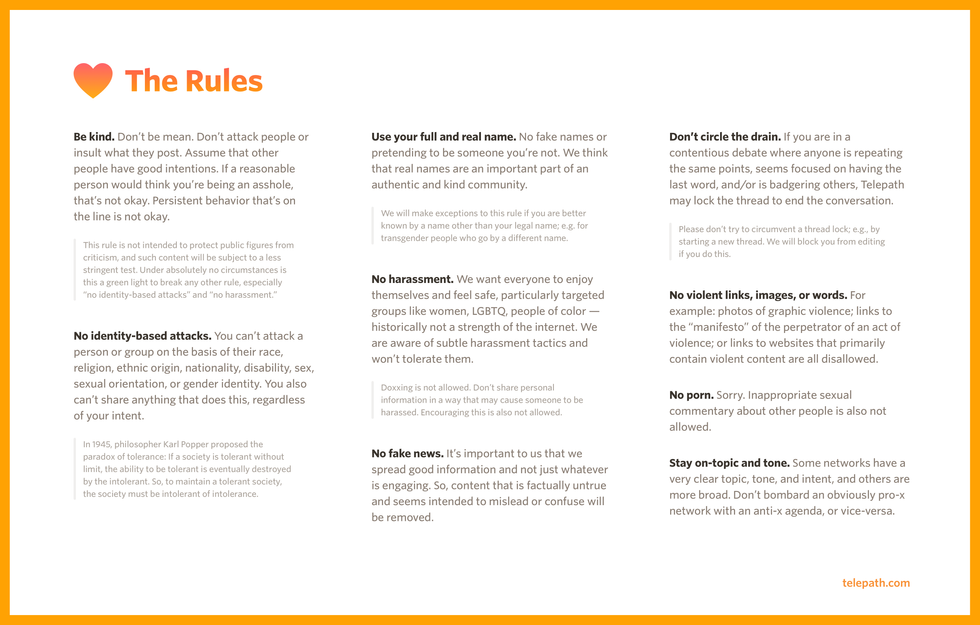

This isn’t particularly remarkable, but Telepath’s big selling point is: an in-house content moderation team enforces kindness, and users are required to display their real names.

Telepath’s name policy is meant to make sure the content moderation team can fully focus on spotting abuse rather than playing whack-a-mole with burner accounts. It’s also a way to humanize conversation. “We require unique telephone numbers and verification so it can’t be a throwaway number on Google voice,” says Tatiana Estévez, the head of community and safety. “Multiple sock-puppet accounts are where you get some of the nastiest stuff on other platforms.”

The policy has already invited some criticism from onlookers who feel it might endanger women and marginalized communities.

“There’s a widely held belief that if people use their legal names they will behave better in social environments because other people can identify them and there can be social consequences for their actions,” says J. Nathan Matias, a professor and founder of the Citizens and Technology Lab at Cornell University. “While there was some early evidence for this in the 1980s, that evidence wasn’t with a diverse group of people, and it didn’t account for what we now see the internet has become.”

In fact, many people who use pseudonyms are from more marginalized or vulnerable groups and do so to keep themselves safe from online harassment and doxxing.

Doxxing—using identifying information online to harass and threaten—is a life-threatening issue for many marginalized people and has soured them on social media like Facebook and Twitter, which has come under fire for not protecting at-risk individuals (though both Twitter and Facebook have tried to make amends of late by removing tweets promoting misinformation, for example). Estévez says that while she’s “very empathetic about this” and that trans people can identify themselves by their chosen name and pronouns, phone-name verification and the app’s invite-only structure were necessary to prevent abusive behavior.

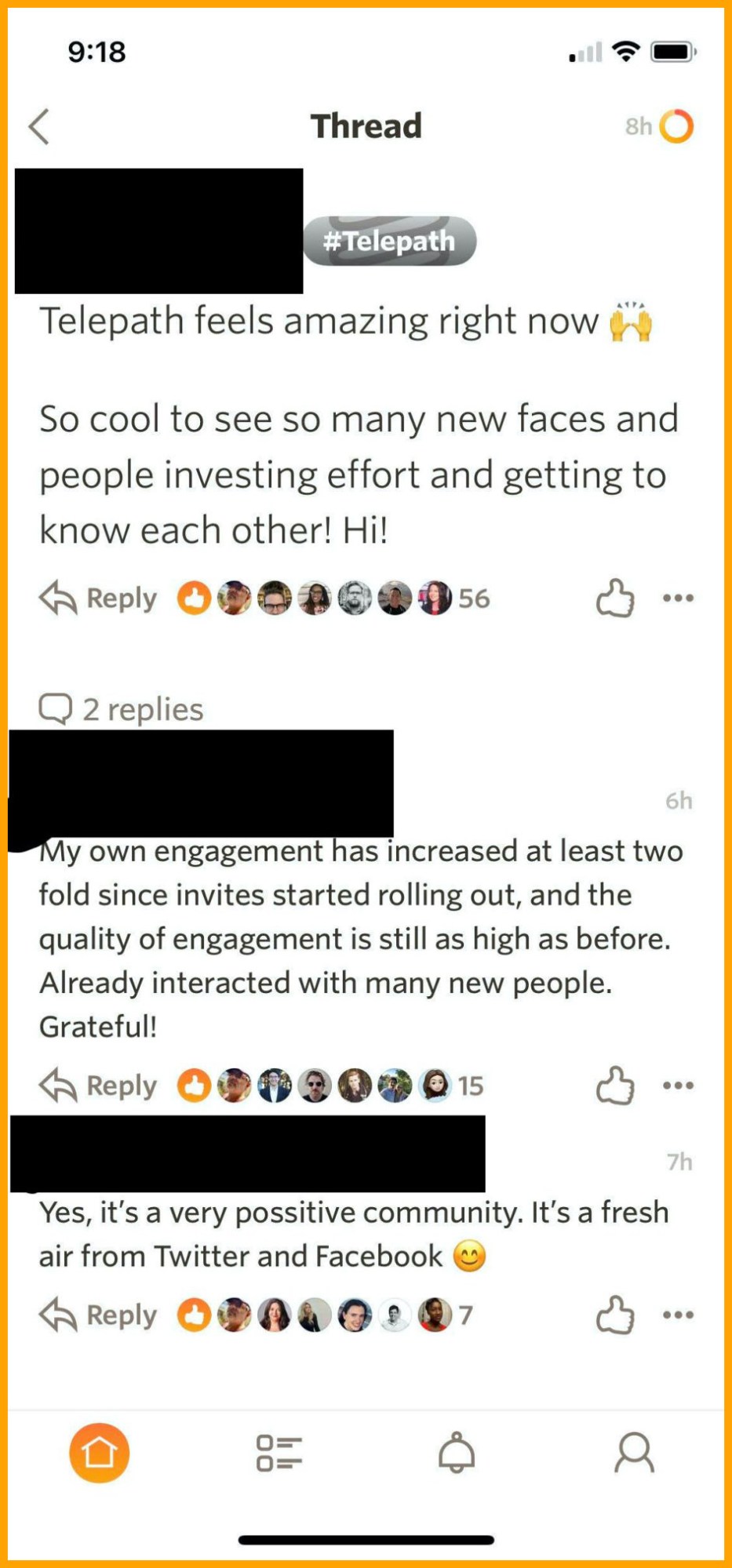

Estévez, who spent years as a volunteer moderator at Quora, imported Quora’s community guideline of “Be Nice, Be Respectful” to Telepath. “People respond well to being treated well,” she says. “People are happier. People are really attracted to kind communities and places where they can have their say and not feel ridiculed.”

Telepath’s team has been very deliberate with its language about this concept. “We made the decision to use the word ‘kindness’ instead of ‘civil,’” Bodnick says. “Civil implies a rule you can get to the edge of and not break, like you were ‘just being curious’ or ‘just asking questions.’ We think kindness is a good way of describing good intent, giving each other the benefit of the doubt, not engaging in personal attacks. We hope it’s the strength to make these assessments that attracts people.”

Historically, platforms have been reluctant to enforce basic user safety, let alone kindness, says Danielle Citron, a law professor at Boston University Law School who has written about content moderation and advised social-media platforms. “Niceness is not a bad idea,” Citron says.

It’s also extremely vague and subjective, though, especially when protecting some people can mean criticizing others. Questioning a certain point of view—even in a way that seems critical or unkind—can sometimes be necessary. Those who commit microaggressions should be told what’s wrong with their actions. Someone repeating a slur should be confronted and educated. In a volatile US election year that has seen a racial reckoning unlike anything since the 1970s and a once-in-a-generation pandemic made worse by misinformation, perhaps being kind is no longer enough.

How will Telepath thread this needle? That will be down to the in-house content moderating team, whose job it will be to police “kindness” on the platform.

It won’t necessarily be easy. We’ve only recently begun understanding how traumatic content moderation can be thanks to a series of articles from Casey Newton, formerly at The Verge, which exposed the sweatshop-like conditions confronting moderators who work on contract at minimum wage. Even if these workers were paid better, the content many deal with is undeniably devastating. “Society is still figuring out how to make content moderation manageable for humans,” Matias says.

When asked about these issues, Estévez emphasizes that at Telepath content moderation will be “holistic” and the work is meant to be a career. “We’re not looking to have people do this for a few months and go,” she says. “I don’t have big concerns.”

Telepath’s organizers believe that the invite-only model will help in this regard (the platform currently supports approximately 3,000 people). “By stifling growth to some extent, we're going to make it better for ourselves,” says Estévez.

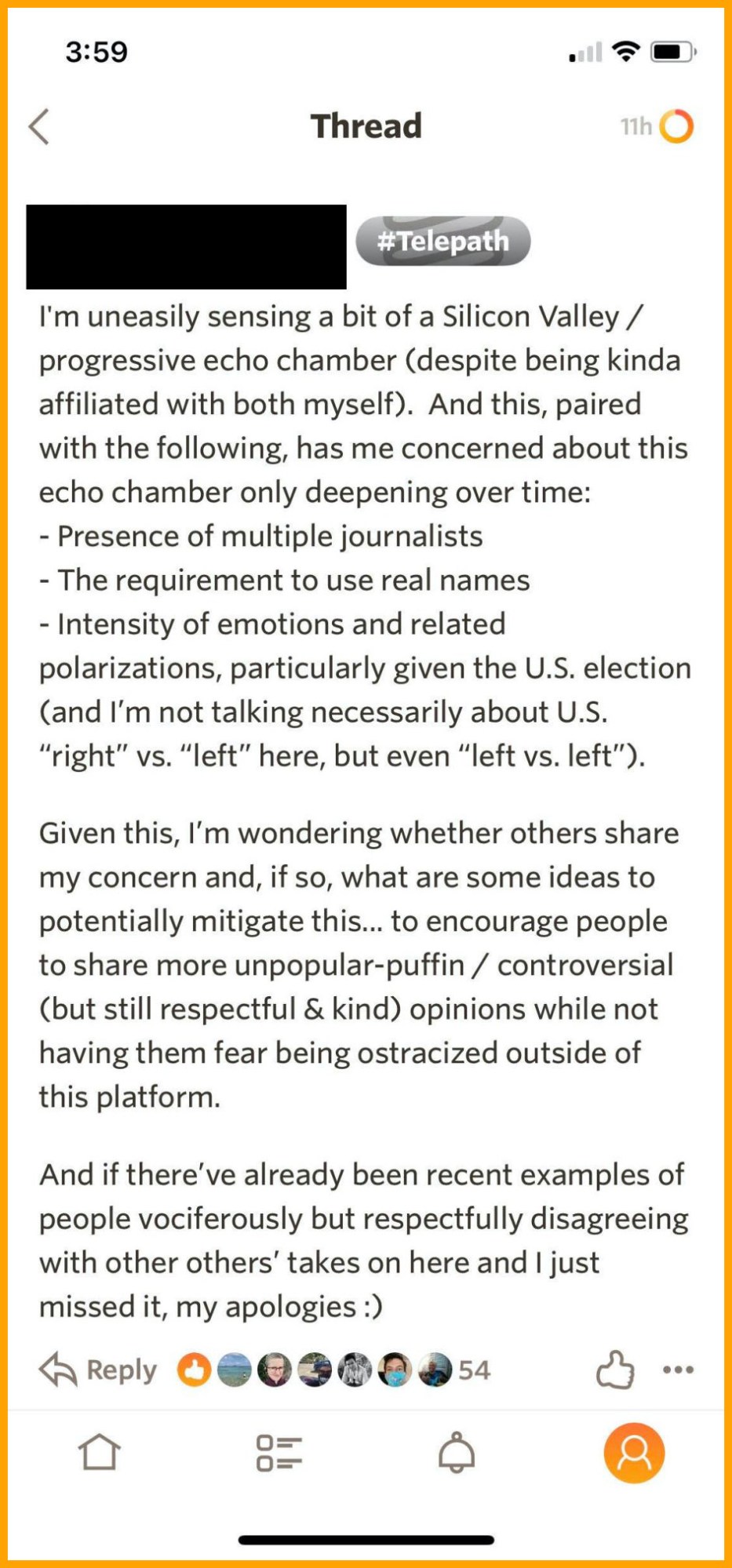

But the model presents another issue. “One of the pervasive problems that many social platforms that have launched in the US have had is a problem with diversity,” Matias says. “If they start with a group of users that are not diverse, then cultures can build up in the network that are unwelcoming and in some cases hostile to marginalized people.”

That fear of a hostile in-group culture is well founded. Clubhouse, an audio-first social-media app used by many with Silicon Valley ties, was launched to critical acclaim earlier this year, only to devolve into the type of misogynistic vitriol that has seeped into every corner of the internet. Just last week, it came under fire for anti-Semitism.

So far, Telepath has been dominated by Silicon Valley types, journalists, and others with spheres of influence outside the app. It’s not a diverse crowd, and Estévez says the team recognizes that. “It’s not just about inviting people; it’s not just about inviting women and Black people,” she says. “It’s so that they [women and Black people] have a good experience, so they see other women and Black people and are not getting mansplained to or getting microaggressions.”

That is a tricky balance. On the one hand, maintaining an invite-only community of like-minded members allows Telepath to control the number of posts and members it must keep an eye on. But that type of environment can also become an echo chamber that doesn’t challenge norms, defeating the purpose of conversation in the first place and potentially offering a hostile reception to outsiders.

Tan, the early adopter, says that the people she’s interacting with certainly fall into a type: they’re left-leaning and tech-y. “The first people who were using it were coming from Marc [Bodnick] or Richard [Henry]’s networks,” she says, referring to the cofounders. “It tends to be a lot of tech people.” Tan says the app’s conversations are wide-ranging, though, and she has been “pleasantly surprised” at the depth of discussion.

“Any social-media site can be an echo chamber, depending on who you follow,” she adds.

Telepath is ultimately in a tug-of-war: Is it possible to encourage lively-yet-decent debate on a platform without seeing it devolve into harassment? Most users assume that being online involves taking a certain amount of abuse, particularly if you’re a woman or from a marginalized group. Ideally, that doesn’t have to be the case.

“They need to be committed, that this isn’t just lip service about ‘being kind,’” Citron says. “Folks often roll out products in beta from and then think about harm, but then it’s too late. That’s unfortunately the story of the internet.” So far, but perhaps it doesn’t have to be.

"Media" - Google News

October 07, 2020 at 04:00PM

https://ift.tt/3jCeVy8

A new social-media platform wants to enforce “kindness.” Can that ever work? - MIT Technology Review

"Media" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2ybSA8a

https://ift.tt/2WhuDnP

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "A new social-media platform wants to enforce “kindness.” Can that ever work? - MIT Technology Review"

Post a Comment