If you aren’t sufficiently broken inside to be an extremely-online journalist — or, worse, a non-journalist who diligently monitors the beefs within the professional posting community — then you probably missed (the latest round of) media Twitter’s brouhaha over Substack.

A tool for publishing newsletters, Substack grew in prominence over the past year as several well-known opinion journalists abandoned their longtime employers to start their own subscription-based, bespoke punditry shops on the platform. In most cases, this proved to be an astoundingly good business decision. There are apparently a great many journalism consumers who aren’t willing to pay $5 a month to support the work of dozens of journalists at a single publication but are eager to pay $8 a month to patronize a single blogger. Combine this reality with the exceptionally low overhead costs of running an email newsletter, and you get a formula for achieving the impossible: a hyperprofitable digital-journalism enterprise. Former Vox columnist Matt Yglesias, for example, is reportedly poised to rake in $860,000 in subscription revenue this year. Unless he’s paying $50,000 a month for his internet connection, his newsletter’s rate of profit dwarfs that of most any major media outlet.

This is a concerning development in some respects. It’s easier for social-media-addicted daily commentators to cultivate loyal fandoms than it is for investigative journalists or state-level political reporters. And yet the latter’s work is generally more indispensable to journalism’s civic function. An ecosystem in which star pundits serve as a major profit center for newspapers, which can then use the revenue generated by their pontificating to cross-subsidize hard reporting, is probably healthier for the Fourth Estate than one in which star pundits reap windfall returns by going it alone. The New York Times isn’t struggling to hire big-name columnists, of course. And there’s presumably a hard limit on how many different paid newsletters the reading public is willing to support. Nevertheless, it’s reasonable to worry about yet another traditional source of revenue for (perennially unprofitable) accountability journalism becoming uncoupled from such reporting. After all, some digital media companies are already ditching conventional publications for Substack’s “superstar independent contractor” model.

But this was not the focus of last week’s Substack discourse. Rather, what roiled media Twitter was the revelation that Substack poached some of its big-name columnists by providing them with a guaranteed minimum income for their first year on the platform. This arrangement isn’t philanthropic. In exchange for guaranteeing Yglesias a base salary of $250,000, Substack reportedly required him to let the platform collect 85 percent of the gross subscription revenue his newsletter generated; had he declined this offer and accepted the standard terms of service available to all Substack users, the platform would have claimed only 10 percent of such revenue. Ultimately, opting for Substack’s star treatment will cost the columnist hundreds of thousands of dollars. It is not clear how many of Substack’s top writers secured similar deals, as the platform does not mandate such disclosure from all the writers it directly finances.

In a much-discussed Substack post, the journalist and fiction writer Annalee Newitz argued that this policy rendered the platform a “scam.” Specifically, Newitz contends that by secretly providing salaries to certain elite pundits, Substack is effectively scamming less-established journalists into thinking that newsletter writing is more remunerative than it actually is. (Newitz also argues that by withholding the names of these elite pundits, the platform is effectively maintaining a secret editorial policy that is contrary to journalistic ethics in principle, and harmful to trans people and cis women in practice. But this is a distinct argument that isn’t germane to my purposes here.)

I don’t find this argument very compelling. But I do think it circles around a genuine problem with the contemporary media business writ large. Before I say more about that, though, it’s worth considering Newitz’s argument in a bit more detail. Here’s how they characterize “Substack’s scam”:

An elite group of Substack Pro staffers, handpicked by editors, have been given the resources to write full time. Everyone else on Substack has to do it for free until they manage to claw and scrape their way into a subscriber base that pays.

Realistically, almost nobody will reach that point. The vast majority of Substack newsletter writers will never make money that’s equivalent to a year’s salary, which is what the staffers get. Instead, they will provide Substack with free content, hoping to get that sweet subscriber cash one day. And Substack will dangle its “successful” writers in front of its rank-and-file membership to keep them going. You too could have a Substack that’s as financially successful as this guy’s Substack! Except you don’t know whether this “successful” Substack was bankrolled by the company or not…We are, not to put too fine a point on it, being scammed.

This critique doesn’t scan to me. It is possible that Substack is secretly bankrolling some newsletter writers who had no built-in audience before joining the platform. But this seems improbable. The few Substack Pro writers who have made their contracts public are well-known commentators who had large, readily monetizable followings before creating their accounts. And this is no less true of the specific Substack writers whose contracts Newitz name-checks. Matt Yglesias does not have a large subscriber base for his newsletter because Substack offered him an advance; Substack offered him an advance because he had a built-in subscriber base for a newsletter. From what we can tell, the root cause of the income gap between Substack’s highest-grossing writers and its typical user is not that the former received downside-minimizing contracts but rather that they were already journalistic celebrities — which is why they were able to secure downside-minimizing contracts.

This doesn’t mean that Substack shouldn’t disclose which writers it is de facto employing. But it does make it hard to see how Substack users are being scammed in the manner that Newitz describes. Newitz erroneously lists Glenn Greenwald as one of the “Substack Pro” writers whose success on the platform could mislead less-established authors. Even if it were true that Greenwald had received an advance: It’s hard to believe that there are very many up-and-coming journalists out there who would see that Glenn Greenwald was making money off of writing newsletters, think to themselves, Well, if an internationally famous polemicist with 1.6 million Twitter followers can make a living off of Subtack, surely I can, too, invest time and energy into launching their own Substack on this basis — and then discover, to their horror, that the Pulitzer Prize winner’s ability to support himself over the platform wasn’t actually a reliable gauge of their own prospects for doing so, as Substack had provided Greenwald with a minimum salary in exchange for forfeiting a percentage of his subscription revenue.

All this said, I think it is true that there are many up-and-coming writers on Substack who are creating content for the platform at an unsustainably cheap rate because they harbor the improbable hope that they will eventually become one of the few who can earn a comfortable living off of such journalism. And I think it’s also true that unearned advantages — which may be opaque to some aspiring Substack superstars — play a large role in determining who does and does not become one of the platform’s elite pundits.

But these particular problems are nearly ubiquitous throughout the journalism industry and do not reflect pathologies peculiar to Substack.

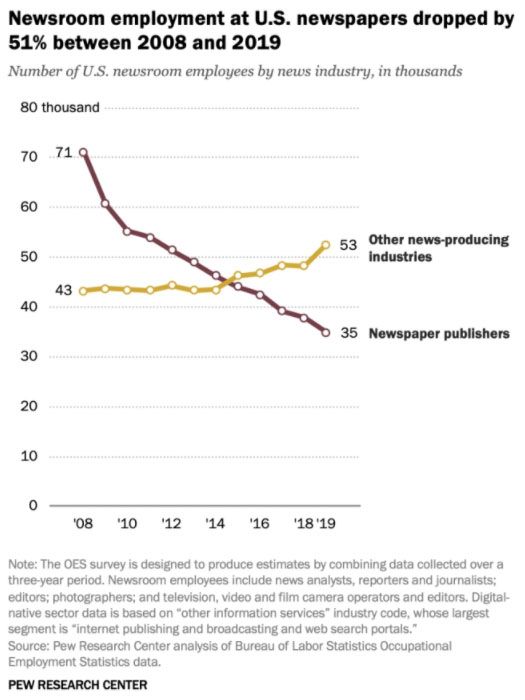

Between 2008 and 2019, the number of newsroom jobs in the United States fell by 26,000, according to the Pew Research Center. Over that same period, roughly 50,000 journalism majors were graduating into the U.S. labor market every year. In addition to making the competition for writerly employment exceptionally brutal, these developments also raised the barriers to merely entering that competition: Since regional newspapers have collapsed faster than national outlets, what jobs remain are now (even more) heavily concentrated in a handful of extremely high-cost cities.

Faced with a superabundant supply of underemployed writers, and increasingly thin to nonexistent profit margins, all manner of media companies in such cities have made a common practice of paying poverty wages for entry-level work. Applicants accept these terms because the outlets offer (potentially, eventually monetizable) “prestige,” and/or because they sought to emulate the success of that publication’s star writers, and/or because they had no other options, and/or because class privilege shielded them from the worst consequences of their underpayment.

Like the vast majority of the writers who create Substacks, the vast majority of the interns who take unpaid to barely paid positions in journalism will never attain the financial security of their publications’ big-name writers. And those big-name writers — and the interns who are able to approximate their success — are typically beneficiaries of an uneven playing field tilted in favor of the upper-middle class. My own path to a decent job in journalism was eased by parental subsidies, which made it possible for me to accept $8-an-hour internships in New York City without suffering malnutrition. The “advances” that most consequentially bias who gets to write for a living and who does not derive from accidents of birth.

The resurgence of labor organizing in media has mitigated the industry’s exploitative treatment of entry-level workers and the class bias inherent to it. And this is one of the many reasons why unionizing newsrooms is a vital project. But labor unions alone cannot solve the underlying problem of mass underemployment within the industry. America does not have more competent journalists than it needs. But it does have far more of them than media firms are capable of profitably employing, amid the erosion of the ad-supported business model.

Which is one major reason why there are so many writers willing to provide Substack with content free of charge.

There may be something distasteful about the fact that Substack benefits from journalists’ financial desperation. But ultimately the core problem here is not that a newsletter platform is helping cash-strapped writers squeeze some tips out of their Twitter followings. The problem is that legions of talented journalists are going underemployed, even as statehouses across the country are going under-covered. Forcing Substack to disclose every contract that it has ever offered will not free us from the scam that is the modern media industry. Only publicly financing the Fourth Estate can do that.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly claimed that Glenn Greenwald had received an advance from Substack.

"Media" - Google News

March 24, 2021 at 06:00PM

https://ift.tt/3cfhN2E

Substack Is a Scam in the Same Way That All Media Is - New York Magazine

"Media" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2ybSA8a

https://ift.tt/2WhuDnP

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Substack Is a Scam in the Same Way That All Media Is - New York Magazine"

Post a Comment